What is Your Body Trust Elevator Speech?

Body Trust is a radically different way of relating to, occupying, and caring for your body in a culture that doesn’t trust bodies.

We recently hosted Sadé Meeks, founder of GRITS Inc, for a four-part learning series with our Body Trust community titled Food as Resistance. Sadé is a phenom and we appreciated the opportunity to learn from her and expand our intersectional analysis to include issues related to food justice and body sovereignty.

Many, if not most, people who worry about how nutrition impacts health spend their time judging people for their food choices or claiming that we are “being poisoned” with sugar or processed or highly palatable foods while knowing little to nothing about the systemic injustices in our food systems.

Image Credit: veggiedoodlesoup/Reb (she/her)

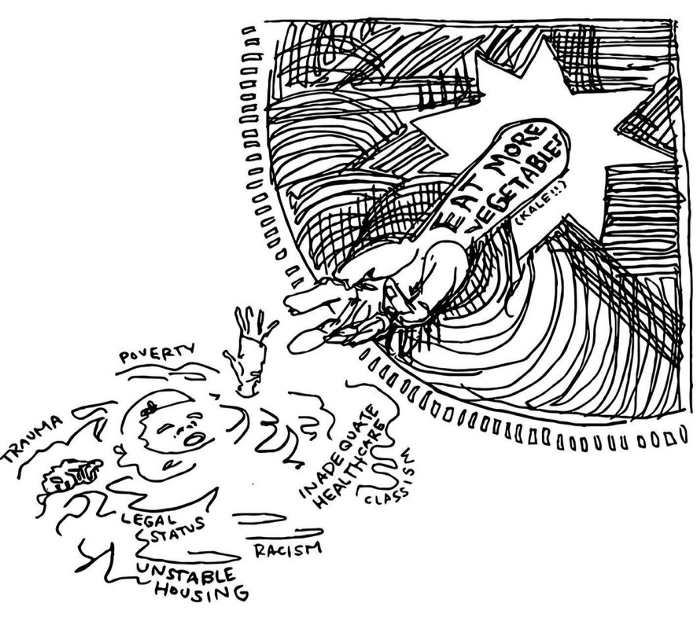

Thinking that people who live with food insecurity mainly experience poor health because they make “bad” decisions about what they eat or how they spend the little money they do have on food, and not about the larger systems of oppression that impede equitable access to food, health services and care, is rooted in white supremacy. Teaching people about nutrition while they do not have access to clean water, affordable food and housing, living wages, etc., does next to nothing and illustrates how dominant culture’s priorities are ridiculously misaligned.

If we want to improve the health of a population, we must prioritize the systemic injustices in our food systems and understand the impact of colonization on what we have come to think of as “healthy eating”. Food justice – the right to food – looks different for every community. Toronto based dietitian Rosie Mensah says:

Racial justice is food justice.

Environmental justice is food justice.

Economic justice is food justice.

Food worker justice is food justice.

We believe in food sovereignty: not just the importance of getting enough to eat, but also a reclamation of power in the food system, rebuilding connection to land and food providers.

“Food sovereignty is the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. It puts the aspirations and needs of those who produce, distribute and consume food at the heart of food systems and policies rather than the demands of markets and corporations.”

– Declaration of Nyéléni, the first global forum on food sovereignty, Mali, 2007

In her recent learning series, Sadé Meeks highlighted all of the ways systemic racism shows up in our foodways: food apartheid (supermarket redlining), injustice (treatment of Black farmers), bias in research, and bias in dietetics. Here are a few takeaways:

“Domestic science represented a more affirmative approach to achieving the same ends by ensuring that white children received proper nutrition and healthy food, thereby becoming physically and mentally stronger.”

The information we share here is just the tip of the iceberg. And it is no surprise that most of the services available to address food insecurity today offer band aid solutions. Food banks are for emergency situations (they are important) and yet they’ve become a way of life, especially during a global pandemic. We need to address the root causes of food insecurity like environmental racism, affordable housing, living wages and more.

We encourage you to check out some of the resources below. Possible next steps will vary depending on your social location, the work you do, and the needs of the people in your community. One action we can all take is to support the Justice for Black Farmers Act.

Onward,

Dana & Hilary

Resources for Our Learning and Unlearning:

Black Liberation and Food Justice

An Urban Farmer Reflects on Food Justice

Growing Resilience in the South (GRITS Inc)

How Black Americans Were Robbed of their Land

Black farmers struggle in face of structural racism and economic headwinds

In 2022, Black farmers were persistently left behind from the USDA’s loan system

High on the Hog: How African American Cuisine Transformed America (Netflix Series)

The Whiteness of the Mediterranean Diet

How to Recenter Equity and Decenter Thinness in the Fight for Food Justice

To Live and Dine in Dixie: The Evolution of Urban Food Culture in the Jim Crow South by Angela Jill Cooley